The rise in tin prices signals a long-term recovery for the

long-forgotten industry. The former CEO of Malaysia Smelting Corp

explains what’s driving the new upcycle and what it will take for it to

be sustainable.

Mohd Ajib Anuar looks tired and drained as he walks into the boardroom

of Malaysia Smelting Corp (MSC). It is a muggy afternoon in Kuala

Lumpur, and the Muslim fasting month has just started. But he snaps out

of his languor as soon as he begins talking about tin, the metal that

made fortunes for many Malaysian tycoons through most of the last

century.

To be sure, the tin business has been viewed as something of a sunset

industry since the mid-1980s. Yet, since the global financial crisis,

tin prices have climbed steadily higher, amid a persistent supply

deficit in the face of growing demand. Now, Mohd Ajib sees a new dawn

breaking for the tin business. “Definitely. No question about it. The

tin industry will grow into a more sustainable industry,” he tells The

Edge Singapore.

Mohd Ajib, 64, has worked in the tin business for more than four

decades. He was CEO of MSC from 1994 to 2013. The 127-year tin smelter

is dual-listed in Singapore and Malaysia, and ranks as the world’s

second largest producer of tin metal. It is controlled by The Straits

Trading Company. Mohd Ajib isn’t planning to fade away into retirement,

though. He has been appointed adviser to the board of MSC. He is also

currently chairman of Malaysia’s Tin Industry Board, and continues to

play an active role in a host of other tin industry organisations.

In fact, Mohd Ajib says he plans to remain active in the tin business

for the next couple of decades, which he believes will be an exciting

time for the industry. Specifically, he wants to help promising tin

companies around the world realise their full potential, and hints that

he is already working on “something big”.

His optimism is underpinned by the expanding uses of tin in recent

years. Take the capsules on wine bottles for instance. The protective

sleeves, which prevent the cork seals from being gnawed by rodents and

other pests as they sit in cellars, were historically made of lead. But

these were phased out due to fears of lead poisoning, and are now

largely made of tin or aluminium.

In May, tin research promoter ITRI launched a committee to push for the

use of pure tin capsules for premium wines at an exhibition in Hong

Kong. “It’s the best capsule for the best wine. It’s non-toxic. The

mechanical quality is good. The chemical quality is good. It looks very

nice,” says Mohd Ajib, laughing at his own enthusiasm.

There are, of course, many other new and less mundane uses of tin.

Notably, environmentally friendly uses of tin have been discovered

through collaborative research by ITRI and companies such as Panasonic,

Sony, Nokia and Motorola.

Today, tin chemicals are used in lithium ion batteries and modern fuel

additives. According to Mohd Ajib, recent fuel additive trials in China

and Peru achieved 10% to 15% energy savings for fishing boats and earth

moving equipment, while carbon emissions were 20% to 30% lower. MSC’s

own subsidiary Rahman Hydraulic Tin has been involved in work on

tin-based fuel additives.

Riding new technologies

Tin has been in use for some 5,000 years, though it was first mined in

large quantities in Cornwall, Britain in the 19th century. In the last

few decades, the story of tin has been shaped by the ebb and flow of new

technologies, and a succession of market crises.

In 1985, tin prices collapsed when the International Tin Council, which

administers a buffer stock used to support prices, became insolvent.

The council was borrowing heavily to keep prices high at a time when

consumption was falling, which encouraged new producers such as Brazil

and Bolivia to flood the market. Meanwhile, in Malaysia, production

dried up as rich alluvial resources were exhausted. In 1995, global

consumption was just 180,000 tonnes, driven mostly by tinplating. Tin

prices at the time had declined to just US$5,000 a tonne.

Nearly 20 years on, consumption has doubled and the price of tin has

risen to US$22,000 a tonne. In fact, tin prices have risen 100% in the

last five years alone. One reason for this comeback was the switch by

the electronics industry to lead-free solder following regulations in

the European Union prohibiting hazardous wastes in 2002. Since then, the

miniaturisation of devices such as computers and smartphones has

resulted in less solder being used in the consumer electronics sector.

Industries like healthcare and defence, however, are taking up some of

the slack.

“The defence and medical sectors needed more time to establish the

durability of the soldering materials. But now that it’s been confirmed

by the consumer electronics sector, they are taking steps to convert to

lead-free solders, and this is where we will see growth,” says Mohd

Ajib. Even so, tin consumption last year was 350,000 tonnes, still below

the peak of 370,000 tonnes in 2007, largely because of the global

economic slowdown and the miniaturisation effect.

Looking ahead, Mohd Ajib figures demand for tin could keep growing as

computers and electronic parts find their way into just about

everything. The automobile sector, for instance, is increasingly using

electronic parts in the vehicles it produces. “So, for tin to show

further improvement in price, consumption and supply, it is not

impossible. Some people say it will shoot up to US$40,000.” ITRI has

forecast global tin consumption to rise at an annual rate of 2% over the

next five to 10 years. Consumption is set to exceed 400,000 tonnes from

around 2015.

Supply constraints

While demand for tin has been strong in recent years, supply has become

more uncertain. For starters, China has turned from a net exporter to a

net importer. That is significant as China is the world’s biggest

producer and consumer of tin.

At the same time, supply from Indonesia, which is the world’s leading

exporter of tin, has become more unpredictable. Small, artisanal miners

account for more than 80% of tin produced in Indonesia. The Indonesian

government has been trying to set standards in the industry, such as

requiring that smelters produce 99.9% pure tin. It has also mandated

that exports be made through the Indonesia Commodity and Derivatives

Exchange. On top of that, the Indonesian government has tried to control

the price of the metal.

The result of all this is that tin exports from Indonesia have become

erratic. “Stocks held at LME [London Metal Exchange] and by consumers

are at historical lows,” Mohd Ajib says. “So, with Indonesian supply

declining and China becoming a net importer, the market is going to move

into greater deficit within the next two to three years.”

While that could be good news for speculators, it isn’t really healthy

for the tin industry over the longer term, according to Mohd Ajib. To

foster higher consumption of tin over the long term, supply has to be

sustainable and prices need to be steady. How can that be achieved? Mohd

Ajib says the key is an industry-wide consolidation.

“Today, you have to buy from small-scale miners… but the global tin

industry will undergo a major shift, transforming the supply structure

from small-scale to more structured producers and a more sustainable way

of production,” he says. The reason is that a significant amount of

capital will be needed to create sufficient supply around the world,

perhaps as much as US$3 billion ($3.7 billion) over the next five years.

And, it is the largest tin companies that will be able to channel this

capital efficiently into proper exploration and mining schemes and

environmental programmes.

“It’s going to be more orderly. Of course, the cost will be higher, but

the electronics industry will be happy to see sustainability on the

supply side,” Mohd Ajib says. In fact, Mohd Ajib figures the price of

tin will have to be higher than where it is today — perhaps US$30,000

per tonne — to sustain production at the level of demand. At current

prices, only a handful of exploratory projects might be feasible, he

says.

According to Mohd Ajib, among the companies that are best positioned to

increase tin supply is Kasbah Resources, which has a project in

Morocco. Other promising players are Australia’s Stellar Resources and

Consolidated Tin Mines. Yet, it will take these projects three years to

prove their reserves before they can start developing the mines. Amid

continued supply constraints, ITRI has forecast a rise in tin prices to a

cyclical peak of US$35,000 to US$40,000 between 2015 and 2017.

Growing interest

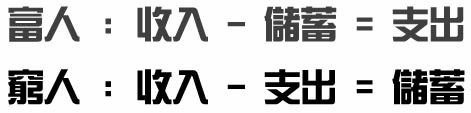

Mohd Ajib began his career at a Malaysian unit of Anglo American. He

later worked for several years at Malaysia Mining Corp, which was

involved in tin, diamond and gold mining. As he tells it, he entered the

tin industry at the bottom of the cycle, when everyone else was trying

to get out. And, it is not that he lacked alternatives, as he was

offered jobs at big Malaysian government-linked companies such as

Petroliam Nasional and Perbadanan Nasional during his early years. “But I

stuck to tin,” he says.

What was the attraction? Mohd Ajib says the tin industry is small yet

very global, and it put him in touch with people all over the world. “I

just like this industry,” he says. “After 43 years, whether I am in

Japan, Korea or the US, I have a lot of friends.” Now, Mohd Ajib is

leveraging some of those global connections and becoming a dealmaker of

sorts, bringing companies that need capital for expansion to investors.

“I am working on something big. I have lots of friends all over the

world. In London, I know all the big brokers,” he says.

Will some of the companies he’s dealing with come to Singapore to raise

capital? For the moment, Mohd Ajib is keeping his cards close to his

chest. Yet, Singapore is a natural hub for tin producers. More than 70%

of Indonesia’s tin exports are sent here for warehousing and

redistribution. Meanwhile, MSC itself counts several thousand retail

investors in Singapore.

Yet, Hong Kong appears to have had the edge in attracting huge mining

companies. In recent years, it has trumped Singapore by winning over the

likes of United Company ­RUSAL, Glencore and Kazakhmys. Mohd

Ajib says if Singapore is to become a listing venue for big resources

companies, a lot more work has to be done to educate investors. “The

resources business, whether it is tin or gold, is a long-term business,”

he says. “The lead time to develop resources can vary from five to 15

years. So, for investors to go into resources, they have to take a

long-term view. Otherwise, it gets too speculative.

Malaysia Smelting may reinstate dividend on improving earnings, but risks remain

Malaysia Smelting Corp’s facility in Penang sits on what could well be

prime seafront land one day. Hidden behind concrete walls topped with

barbed wire, and located close to the Penang Bridge, it started out more

than a century ago processing tin ore from mines in Perak and Selangor.

These days, MSC has a much wider global network. On a sunny afternoon

in June, bags of tin ore from mines in Congo, Rwanda, Bolivia, Myanmar,

China and Mongolia were piled chest high on the floor of the plant. Out

in the yard, neat stacks of shiny tin ingots waiting to be shipped out

gleamed in the sunlight.

Chua Cheong Yong, CEO of MSC, says the company’s financial results are

regaining their shine too, thanks to a sharper focus on its traditional

tin smelting business in the last couple of years. However, growing that

business over the long term is becoming more difficult, because of the

increasingly limited supply of tin ore.

Malaysia’s tin mining business pretty much died in the mid-1980s, amid a

slump in tin prices just as the country’s once-rich alluvial deposits

were almost exhausted. A decade ago, MSC began trying to move upstream

to secure its own supply of tin ore. In 2002, it took a 75% stake in

Indonesia’s PT Koba Tin, which has a mine on Bangka Island. Two years

later, in 2004, it acquired Rahman Hydraulic Tin, which operates

Malaysia’s largest open-pit alluvial tin mine.

MSC also made a bid to expand into other commodities. In 2007, it

bought stakes in mines in Australia, Canada, Indonesia and the

Philippines that produce copper, gold, zinc, silver, nickel and coal.

Its timing couldn’t have been worse. The following year, commodity

prices collapsed in the wake of the global financial crisis. In

addition, the family of the late Tan Chin Tuan tightened their grip on

The Straits Trading Company, which controls MSC, and embarked on a

strategic review of the whole group.

MSC was directed to focus on tin, and it promptly began offloading the

non-tin mining assets it had only just acquired. Then, in 2012, PT Koba

Tin ran into trouble when it failed to extend its contract for work, in

spite of renewal guarantees. The Indonesian government also hiked export

duties on tin ore from 5% to 30%. MSC decided it wasn’t worth hanging

on to PT Koba Tin, and sold its stake in June.

The silver lining is that the string of impairment losses that MSC

suffered over the last few years will finally come to an end. “By June,

we would have taken out most of the hit,” Chua tells The Edge Singapore.

“Now, operations will be very much driven by smelting, marketing and

trading and [tin] mines, which have shown resilience in riding the

downturn. We need to build up confidence again.”

In 1Q2014, MSC reported a 2% decline in earnings to RM14.7 million on a

2% rise in revenue to RM429 million. The company hasn’t declared a

dividend since 2012, but that could change soon. “We are looking to

distribute dividends again,” says Chua. “In the short to medium term, we

are looking to stabilisation. In the mid to long term, there is

potential to develop.”

Expansion plans

How does Chua plan to grow the company? One idea is to broaden MSC’s

business to include tantalum and tungsten, which are related to tin.

“The market for tantalum and tungsten is one third or a quarter the size

of tin, but their valuation is good. They occur together and share the

same supply network. There is nothing to stop us from trading tantalum

and tungsten since we have a strong marketing network in the

Asia-Pacific,” he says. “They will support our mid- to long-term

growth.”

Chua also wants to expand MSC’s tin mining operations. However, after

its unpleasant experience in Indonesia, he says MSC will focus on

Malaysia and “regionally accessible and more-friendly countries”.

Notably, it has carefully nurtured Rahman Hydraulic Tin into a money

spinner. The 107-year-old mine was losing money when MSC bought it a

decade ago. Last year, it made RM34 million ($13.3 million) before tax,

up 17%. Now, it is poised to grow bigger. In March, Rahman Hydraulic Tin

acquired an 80% stake in SL Tin, which holds a mining concession in the

state of Pahang.

MSC has also been laying the ground to secure mining concessions in the

strife-torn Republic of Congo. While the United Nations has introduced

sanctions to cut off funding to rebels fighting the government, MSC has

initiated a scheme to certify non-conflict tin from the country.

According to Chua, tin produced in Congo is now traceable each step of

the way from source to smelter. MSC itself has been audited three times,

the last audit being in May. MSC also owns a 40% stake in a smelting

plant in Lubumbashi.

Much of Congo’s tin is produced by artisanal miners, who lack the

resources to make big investments to increase production in an

environmentally sustainable way. However, Chua is hoping the day will

come when the Congo government allows big mining companies to gain

access to its mineral resources. “Africa has huge potential if we get

our strategy right and the government does not sway away from

development,” he says.

Long-term risks

Chua joined MSC right out of university some 30 years ago. Among his

earliest tasks at the company was buying tin ore from miners in Taiping,

in the state of Perak. He worked his way up the ranks, and was

appointed CEO on Dec 31 last year.

Looking ahead, Chua is candid about the risks MSC faces. While the

company is working to secure as much supply of tin ore as possible, he

says tin producing countries will eventually want to set up their own

smelters and take control of their mines. “Resource nationalism is very

real today,” Chua says. “We have to take a view on tin price and

sovereign risk before we go into a project.”

Some market watchers also fear that MSC’s controlling shareholder has

little appetite to fund major acquisitions. They point out that

Australia-listed Kasbah Resources, which has the most advanced of tin

projects in the pipeline, is currently trying to raise some US$100

million ($124.5 million) but failed to get MSC to come in as an

investor. Kasbah Resources’ shareholders include International Finance

Corp, Toyota Tsusho and Thai smelter Thaisarco.

When approached for comment, however, a spokeswoman for Straits Trading

says the group wants to see MSC grow. “Straits Trading will support MSC

in any initiatives that will create value for shareholders,” she tells

The Edge Singapore. “Straits Trading will be supportive of MSC in its

quest to enhance its position in the tin industry.”

Whatever the case, with MSC on the road to profitability and likely to

reinstate its dividend, its shareholders are likely to see better times

ahead. And, even if the company’s tin business doesn’t grow much, the

land it occupies in Penang will certainly rise in value over time.

The Edge Publishing Pte Ltd

Document EDGESI0020140805ea8400008